Interoperability

For historical reasons, phone numbers and email have a very useful property: interoperability.

Interoperability is an idea in electronic systems, which has largely been forgotten in our modern technical world, which is dominated by gigantic corporations looking to extract every nickel from your every digital move. The story of how we got there is worthy of a read, but I'll try and give the quick hits here.

Alexander Graham Bell invents the telephone in the late nineteenth century, and in true American fashion immediately establishes one of the most ruthless monopolistic corporations to ever exist: American Telephone and Telegraph Company (AT&T).

In 1913, AT&T bought the other telecommunications monopoly Western Union, who had consolidated the telegraph system as the telephone took market share. This was a little too close in time to Teddy Roosevelt's trust bustin' movement, and brought about the ire of the US government.

Faced with commupance from the federal government, AT&T negotiated an out of court settlement called the Kingsbury Commitment. The Kingsbury Commitment forced AT&T to divest itself from Western Union, and, important to our phone number story, forced them to allow smaller networks to connect to their long-distance infrastructure. This required AT&T and the other networks to start down the path on standardizing some sort of protocol for keeping their identifiers unique, and interoperable.

And thus the phone number was born. Of course phone numbers existed before then, and the history of how they worked before these networks got so large that everything was automated is actually pretty interesting (see for instance Julia O'connor, and the Strowger switch), but for our story here there are two things of note. First, this was the first time that a unified numerical identifier was granted to people by a non-government entity, and two to make up for AT&T having to share its network, the Kingsbury Commitment made it so that AT&T could boot unauthorized connections to its network.

Banana phone

|

|---|

| The Carterfone was a work of art |

In the sixties, Thomas Carter invented the Carterfone, a device which was essentially a walkey-talkey connected to a phone receiver so folks could talk via radio to other folks on a phone. AT&T magnanimously told Carter to pound sand when he tried to use their network. Carter, whose invention was made for oil field workers so they could call for help when away from phone lines, took the issue to the FCC.

By the time Carter's case reached the FCC, the agency had started to recognize the need for computers to connect to each other. They used the carterfone case as an opportunity to revisit AT&T's ability to block devices from connecting to their network. AT&T was faced with a similar reality.

Recognizing that connecting computers might just be lucrative enough to warrant competition against AT&T's network, AT&T and the FCC use the case as an opportunity to open AT&Ts network, for a modest fee of course, to the rapidly growing networks of computers popping up around the country. The Law of Unintended Consquences being what it is, Carter's case led to two decades of AT&T dominance, and then it's breakup in the early 80s.

I had to track down a picture of Thomas Carter to see what this legend looked like. I was not disappointed.

It doesn't get much more American than some guy jury-rigging a way for those in the oil fields of Texas to phone home to let their people know they haven't blown up yet that day taking on the largest company in the country, and winning so that it can ultimately make more money.

Multi-user

These newfangled computers that were using AT&T's network to talk to each other had a problem though. Unlike humans that have distinct voices, the machines all talked the same. So to have any reasonable notion of who was behind the machine, we had to introduce auth.1

Nowadays there are a lot of auth protocols, but back in those days it was good ol' username and password. You need both because passwords can't be unique, and usernames don't need to be secret.

This auth-tuple can't be shared between things that need to be logged into since those two things can't trust each other. This means different online things can't just assume that you username in one system is the same as the same username in another system. And thus, almost by definition, being user on a computer at the time meant giving up on interoperability.

America goes online

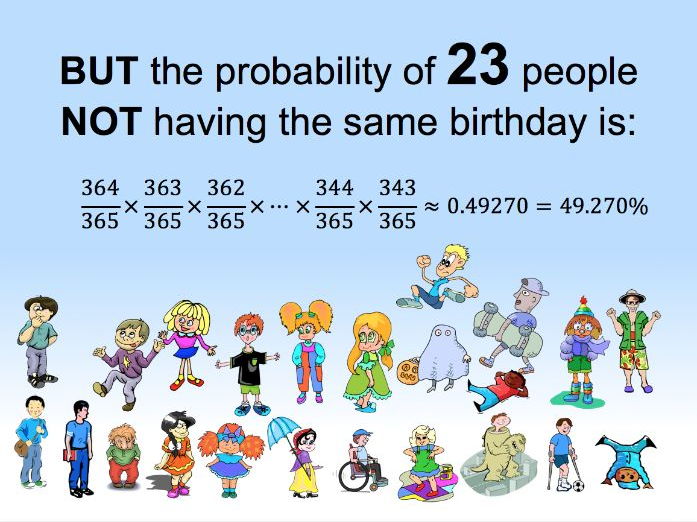

There's an interesting problem in statistics called the birthday problem. It shows that you only need 23 people chosen at random to have a greater than 50% chance of two of them having the same birthday. The reason for this comes down to some simple math.

Probabilities are usually represented as fractions less than one. In this case, if we had only two people the probability that they would not have the same birthday is 364/365 since there are 364 days the second person could be born on that would be different than the first person's birthday. The third person would then have a probability of 363/365 instead because now there are two different days that people have birthdays on. You continue ticking down the numerator for each person added to the test.

To find the total probability of this series of probabilities, you just multiply them all together, and when you do that for 23 people you get the probability that two people will have the same birthday just over 50%.

What does this have to do with the price of beans in Boston?

Well that whole username and password thing was working just fine for computers connecting to things, but as the number of people grew, people started birthday probleming their desired usernames. There are somewhere around 20,000 common six-letter words in English. You know how many people need to be selecting words before there's a 50% chance of two people selecting the same one?

167

Those of you who are known as ponies724 know what I'm talking about.

This wasn't so bad when there was just one thing to sign into, but as places with usernames proliferated you had to deal with someone snaking you on ponies724. Then you'd have to remember not only your password, but which incarnation of your username to use. Zweibel is German of onion, but it's also two-bell. So when it's taken I use Dreibel (three-bell). There's even one place where I'm Vierbel (four-bell). I don't remember where that place is, but I remember it's out there somewhere.

So the online folks went searching for a "username" that was unique to the user so they could carry them around with them. Something cheap, and easy to give to anyone. Maybe something where ponies724 could just be ponies alongside other ponies. Something like email.

You've got mail

Listen, I was there. Hearing the digitized low-fi voice of Elwood Edwards 2 was awesome, and the first few emails you got were so novel and cool. But soon there would be such a deluge of emails that had to be forwarded to ten friends to avert disaster, that it was impossible to keep up. Obviously those were all spam since nothing bad has happened since the mid 90s...

Email was then, and mostly still is now, the simplest open and interoperable thing that exists in cyberspace.

All you need is a domain and a computer, and you can set up an email server. Now if you lookup how to do this you'll find a lot of things telling you not to, and the reason for that is that nowadays there're a ton of hoops to jump through to make it so that your emails actually go through. But I can't really tell if that's to keep the spam out, or to keep the people beholden to the email giants who are gatekeeping this in the first place. I mean, how do you feel they're doing at keeping out spam?

Email and/or phone number

Email served almost like the phone number for users. It became a single identifier that people could use everywhere, but the systems it was being used with weren't connected together--or at least weren't connected in a way that would benefit users. But we need to get to the next millenium to start filling in that story.

Once the internet got going in full swing, AOL started to lose its shine, and people started looking to alternatives for email. Hotmail, and Yahoo were the major players of the late nineties, and a lot of people jumped over. There were other factors of course, but the incredible flood of users claiming free emails is partly what fueled the dotcom bubble that saw Yahoo with a market valuation of $125 billion, and made Microsoft the highest market valued company in the world (do you see a trend here?).

Then in 2000 the bubble would pop, and as so often happens the human phoenix of innovation would rise from the ashes. And as so doubly often happens, that phoenix would exploit the masses for profit.

"auth is short for authentication (authn) and authorization (authz). The former establishes who you are, and the latter establishes that you are able to do what you're trying to do. I like writing about auth, which is why I'm going to leave this as a footnote, and not add fifty paragraphs to this post."

"Elwood was paid not one, but two cool Benjamins for his recording of perhaps the most well-known voice acting of the 90s."